How to build an idea-generator

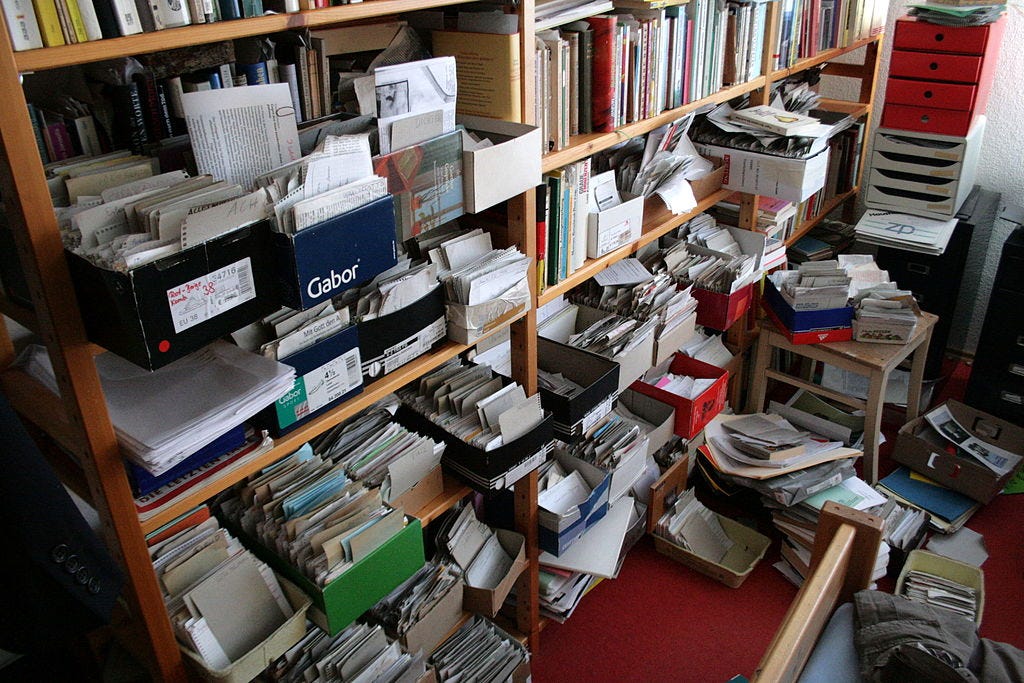

It’s not a secret that I keep notebooks containing the random things I come across (the photo above is an assortment of some of them). These books include notes from what I read, hear on podcasts or find in articles. Within these notebooks, I also jot down my ideas.

I started over a decade ago when I’d just gone back to university to work on an advanced degree. At a ‘how to be a successful grad student’ workshop, one session was on keeping a notebook. They advised us to write everything down from the content of research articles to our grocery list in one place. We’d have a record of our research that wasn’t precious and we’d offload the contents of our mind to free up space for thinking. When the time came to write out thesis, the notebooks would be the starting point—at least that was the theory.

I took this advice to heart—I filled multiple notebooks for both my Masters degree and my PhD. The single notebooks morphed into separate ones for my non-research related stuff. Now I have stacks filled with notes, including these gems (found by a random flipping through)

On the International Space Station, fresh fruit and vegetables seem to rot faster than on Earth (from Endurance: A Year in Space. A Life of Discovery by Scott Kelly)

From 4 January 2012 - What do you get if you cross and snowman and a vampire? (Frostbite) a bad joke found in a Christmas cracker.

Sepia means and ‘cuttlefish’ in Greek after an ink made of dried cuttlefish with a colour between red and brown.

Or this quote by Ursula Le Guin - “If you see a whole thing—it seems that it’s always beautiful. Plants, lives,… but up close a world’s all dirt and rocks. And day to day, life’s a hard job. You get tired. You lose the pattern.”

So ten years on, I have a delightful pile of notebooks filled with random stuff. Stuff that I chose over the years, stuff that probably clusters around themes I don’t yet see. Stuff that might make interesting articles, fodder for my next scifi story, or even a non-fiction book. I’m sure they all add up to something. I just don’t know what.

I actually quite enjoy filling my notebooks, but I’d like to mine the contents better. I’ve always noted where the contents came from. About five years ago, I started adding page numbers for ideas found in books. About a year ago, I started adding indexes (based on bullet journal ideas). My notebookery is improving.

Stumbling upon How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens shows the next level of note taking. This method is based on Luhmann’s (a prolific sociologist) slip-box and here’s how it works.

Whenever Luhmann read something, he would make a brief note on the topic on an index card—always sticking to a one idea per card. He’d then put the card into a ‘slip-box’. The next time he put an idea on an index card, he’d look in his slip-box for other relevant notes. He would file the new card with links to existing notes, creating a web of connections.

It’s the connection between notes that’s important—this is where insights and more questions form. Notes expand our brain's capacity and can become the mechanism of our thinking.

In time, the cards would form a complicated web of connected ideas. He’d then mine his slip-box for topics to be delved further into or put together into publications (he was an academic, after all).

This non-linear system would allow its creator, in time, to build a highly personalized idea-generator.

“The more you learn and collect, the more beneficial your notes should become, the more ideas can mingle and give birth to new ones.”

How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens

In theory, the material in a slip-box will cluster around themes the creator is interested in but may not actually realize. The slip-box can bring forward forgotten ideas, or even remind us we’ve had the same idea multiple times (this happens to me). It creates a place to juxtapose and tinker with ideas, allowing new patterns to form the web of associated information.

Here's an example of what the physical version of this system might end up looking like:

I like the potential of the slip-box method because I’d love my own personalized idea generator. But maintaining a physical box (or drawers of them like old library files) seems a bit much for me. However, there is software capable of the task. I’m now futzing with different options to get my system going (I’ll report back on how it’s going).

As a tangent, in the book there’s a reference to half of all doctoral theses staying unfinished. Sadly, I'm not surprised. Fortunately, I finished after what felt like a really, really long time.